FAIC Oral History Interview: Session 4

- Apr 27, 2021

- By Stephen Cole

- In Interviews

Conducted July 25th, 1985

Karen discusses the Centre’s position on the use of adhesives, and her experiences working on the UN curtain restoration in Sweden

Karen made several handwritten changes to the transcripts after the interviews were conducted. These were mostly minor edits for legibility or clarification, but in some instances she added additional information or corrected herself. We have highlighted these instances in the text, and you can use the toggle above to turn the highlights on or off.

Well, this is our last session, and I’m going to change the subject from last week’s adventure on the roads, to the Centre’s moderate position on the use of adhesives. I was wondering how you felt, because in conferences, the Centre does put across this moderate view that they will use adhesives if necessary, the last ditch effort, but stitching is encouraged.

Yes. Well, of course, I suppose you could say that all the work at the centre is based on the experience that I have accumulated over the years. And since I was one of the first people to use adhesives, I was also one of the first to discover some of the drawbacks. Most especially because the work that I did after I left the Victoria and Albert Museum was for the National Trust and Historic Houses in general where objects are displayed in open condition. And that meant that all of the drawbacks, well perhaps that’s a bit strong, that most of the drawbacks became obvious within a fairly short time, anything between ten and fifteen years. It involved such things as the static quality of most plastic adhesives, which attracts dust and dirt from the air and some of it gets really embedded.

As in your article about Mary’s Christening dress?

Oh yes.

That’s a good example of what can happen?

Yes. The dress worn by Mary Birch in 1812 when she was four years old. It was given to the Geffrye Museum by her granddaughter.

Mary Birch, that’s right.

The affinity between the consolidant and carbon block. Yes, it was quite a shock to us all. Many factors combined to make the conservation truly irreversible. The same with the Soho tapestry. I have no doubt this work too was believed irreversible by the conservator. There was no report. We were told it began to look unsightly after less than a few years. I told you about that?

Yes, I’ve forgotten which publication it was in, though.

There were two given at Italian Textile Conferences. We were able to undo the damage this time, but it could have been necessary to write the tapestry off. The adhesive had grown brown and brittle. The fact is that from the point of view of reversibility, a tapestry is a large thing, and will require enormous quantities of solvents. In this case, acetone. We had to do the work outside, well away from the palace. We had the security officer standing by, and the firemen of the Palace. Kingston ambulances and fire services had been alerted. Mishaps could have been very very bad. We were lucky. We managed to get through the day without incident. But we had to promise never to undertake such a job again. I still get scared when I think of the danger we were courting.

From the palace security point of view?

Yes. Think of it! And from the point of view of health risks to the people who work were involved with handling the solvents. Another thing – it’s obviously impossible to talk about reversibility when you come to deal with objects that size. And knowing that to reverse it you need huge quantities of solvents. To immerse that tapestry in any kind of solvent we worked out that it would take fifty gallons to cover it with one inch. And that was only one bath! Really of course, it is totally unnecessary to ever think of using adhesives when you’re dealing with wool, because wool is very very rarely in a condition where it would flake away by touching it. It’s a totally different thing when it comes to military flags that may sometimes consist of dust and some painted areas. You can’t stitch into paint. I think that in such cases you would be justified to stick. We have found a way though of being able to keep particles of dust between layers of crepeline, that makes them look good as a flag, but I think that conservators have to be totally aware of the fact that using adhesives really is the end of the road for an object. It will only last for as long as it looks good with that final treatment. Depending on circumstances the adhesive begins to flake off after a certain time. It usually cross-links whatever the test beforehand. It attracts dust and dirt, as I said. It won’t look good for very long. And then there’s nothing you can do about it. So, I wouldn’t ever use it on anything that can be stitched1.

One thing that I must say is, you’re very open and honest about the problems and mistakes in the past and Mary Birch was just one of those examples. Is that something that you feel is important?

Well, I believe that if we want to think of ourselves as belonging to an emerging profession, we have to have the honesty and integrity to admit when we go wrong. And I also think that if you get stuck in a groove that you can’t leave, obviously you can only be waiting for your pension and that’s the end of that. I hope I’ll never come to that. I think that one must keep up with the times while never forgetting that conservators are expected to keep the objects intact without interfering with their built-in evidence – whatever the fashion of the day.

I’ve been thinking about stories that you’ve told. And this goes to the stitching side of it. I heard something about someone who used their own hair for stitching.

Ah, Louisa Bellinger did that. Excuse me just one second.

Well, just a small business matter and we’re off again.

Oh, yes, about Louisa Bellinger.

Oh, it was Louisa?

Yes. Because it has really always been quite difficult to find materials for us and in the beginning it was particularly difficult because more and more fine materials and needles and stuff were going off the market.

And this is about when, would you say?

In the late 1950s, 60s. So she discovered that she could use her long hair, which was just changing from brown to grey, to white, so she was always able to find the right colour (laughs).

Oh, that’s wonderful.

Yes. She prided herself on that.

And how did it work?

I expected it would work very well, because after all hair has been used for many things, including hair embroideries, as I’m sure you know. I don’t know whether human hair attracts as many creepy crawlies as it seems that goat’s hair does. But I expect that it would still be quite alright.

Can you think of any other sort of stories of people or yourself that might be of interest?

Well, do you know about when we did the United Nations tapestries?

No.

They had been woven in Sweden as the gift by the Swedish government to the United Nations.

I think I’ve seen them in New York.

You may have. Well, they began to fall to pieces, we were told, about a year after they were put up. Wool weft and linen warp. It shouldn’t have happened. Ten years after they’d been finished they were taken back to Sweden. I think that it was thought that in some way, the manufacturer was responsible. We had a Swedish student working with us then, and she suggested that I should be asked to go to Sweden and think of what could be wrong. And I did. This was in the workrooms of Märta Måås-Fjetterström, and they were run by Barbro Nilsson.

That’s a very famous workshop, yes.

It is, yes. And it was quite clear to me knowing about the workshop the way that I did, that there could never be any question of them being at fault in any way. So it had to be something else. Anyway, I arrived in Sweden to stay in the most marvellous house, called Nordhem on the coast, near the coast.

On the west coast?

Yes, near the workroom. I was invited to be with Eva-Louise and her mother Soli Svensson, who now lives in England, both of them.

Eva-Louise?

Svensson. She’s now Eva-Louise Pepperall. And she was the one who put together the courses that Stephen Cousens and Caroline Clark attended in tapestry weaving at West Dean College. I’ll tell you about that afterward. Anyway, to come back to the thing in Sweden. So I went to this beautiful weaver’s house and they had spread the tapestry out for me to look at. And it’s very big. Two curtains. Seven metres by fifteen metres each.

And these were done in tapestry technique?

Yes, yes.

How unusual.

Yes. They were quite quite beautiful, even in the sad state they were in, they were still very beautiful.

How were they… were they…

They were just simply falling apart, everywhere. Not just one colour.

Not just the warp, the weft also?

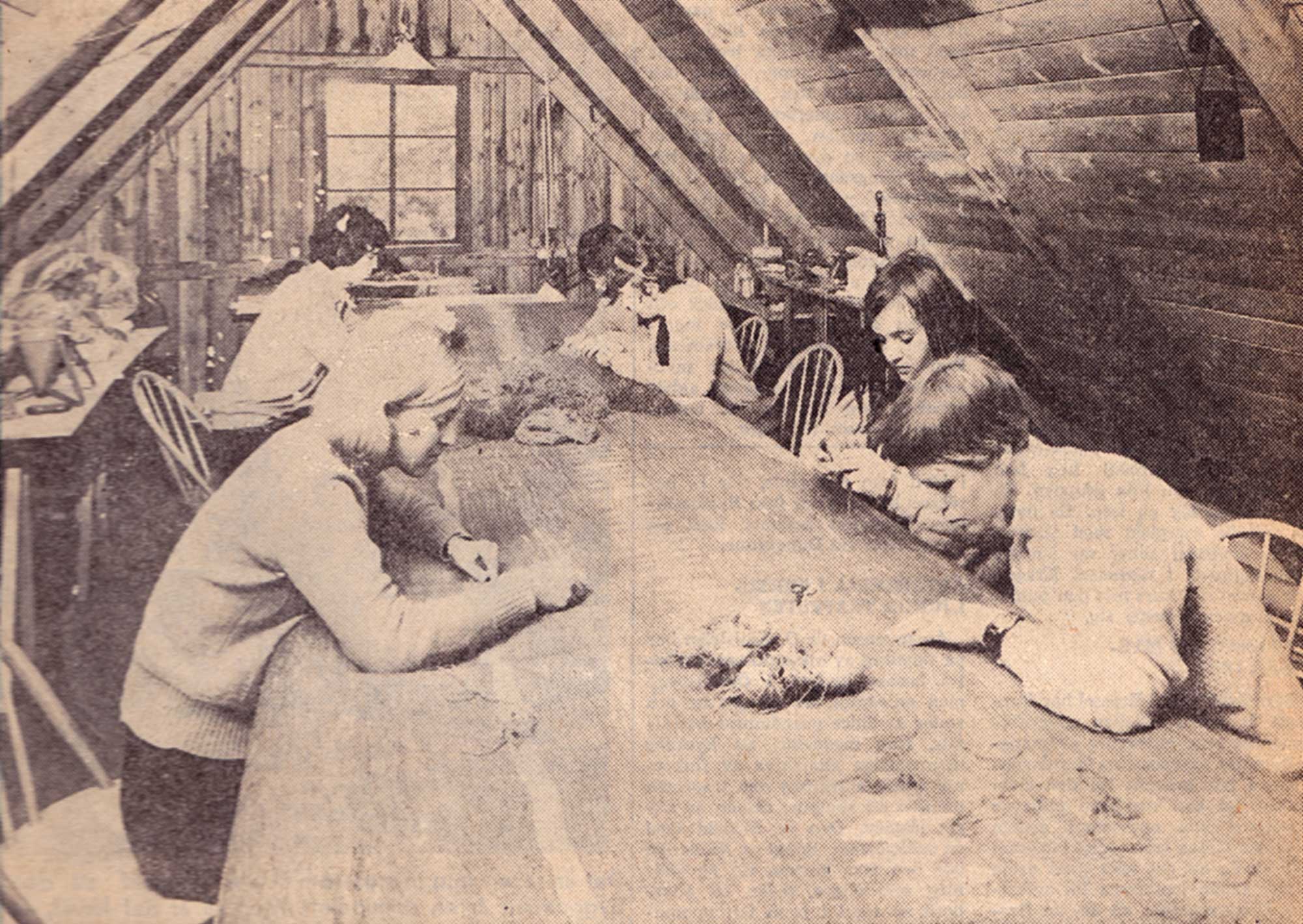

Yes but in particular, the wool. And in order to examine the tapestries I had to get close to them of course, and they were so big I had to crawl on them to get close enough. And it didn’t take more than a few minutes before big red bumps came out on my arms. I’m not very susceptible to that kind of thing, so that was a bit strange. So I thought it has to be something to do with a chemical reaction not known to me. I suggested that we get it tested by the Swedish Textile Research Association. I also took a piece back to London. I gave it to the National Gallery, where Joyce Plesters tested it. The pH was below one. So why? Why would that be? And the answer came practically immediately. All textiles hung in public buildings in New York must be flameproofed. And works of art appeared not to be exempted2. I got mad about this and said why didn’t anybody find out that wool does not need flameproofing because it can’t sustain burning? Ah, it’s stupid, you know, to get upset about bureaucracy instead of trying to educate it to do a little thinking when confronted with special circumstances. Flameproofing for theatre textiles or something equally ephemeral should never be considered suitable for works of art. With the impetus of rage, I then put together I put together an article for Studies and sent it to Garry Thompson who was then the editor, and he was on the phone immediately on receipt and said, we can’t publish this, we’ll be sued. I said I haven’t said anything but the truth. And he said, no, but that is immaterial. Would you like me to rewrite it? I said, yes please, and then he did. And then a little piece appeared just so that people’s attention could be drawn to the fact that flameproofing could not be considered an appropriate treatment for any textile of cultural or historic importance. That was one thing dealt with. The next thing was trying to do something about the damage already done. Funding was available by the Swedish government for conservation and Eva-Louise and her mother and I put together a sort of operation to save the tapestries, which involved doing the work in their beautiful house in Nordhem with its big gardens and getting people together to come and work on the project. So we began by washing it. It was in June and it was raining. And we had to get the water from the well, and it was very very cold, and the only way that we could deal with the washing was making a large bath on the lawn. And then we had to try to neutralise the acid before immersing the tapestry3. We did that by rubbing in an enormous amount of bicarbonate of soda and then swilling that out as fast as we could. We began by collecting a lot of water in preparation. And I’m glad to say that we got it to neutral after the first immersion. This was the introduction to cleaning. We then washed it and it was dried. And the people who helped came from Japan, India, South Africa, Holland, England and America as well as Sweden and Denmark. The next thing was getting together on finding a way of doing the repair. We decided there to use resin-coated net for support and had a frame made for the tapestry in the loft of the farmhouse.

Fifteen metres?

The curtains were woven in two parts, they had both been woven in two parts and we were able to separate these for the repair. Our greatest problem was that we could only put this net on in sections, overlapping sections, to be stitched together as we went along, in order to have something to secure the tapestry onto. It took three months to do that by a team from absolutely all over the world, and now including a Japanese student. Did I say South Africa? We had a truly international team.

Were they supplied by the United Nations (laughs)?

No, it was students who had worked with me over the years. I had taught them all. Except for the Indian boy. He was a fellow student from Eva-Louise’s art school in Stockholm. But otherwise they had worked with me before, so they all knew what it was about. And were willing to pitch in and do everything. We got up in the morning at 5 o’clock and worked for four hours. Spent the middle of the day on the beach and then another stint later in the day. And Eva-Louise’s mother did all the cooking and it was fantastic. It was altogether a really amazing experience.

How long did this take?

It took the whole of the summer. Unfortunately our work changed the dimensions of the tapestry.

The washing or the netting or all of it?

Both, all of it.

The team repairing the UN curtain in the loft space. Left to right: Michael McGreal, Rinske Driesens, Naoko Futami, Margaret Louttit, Susan Grabowska, Eva-Louise Svensson.

And the fire retardant, probably.

Yes. That was the cause of it all. So I believe that the curtains are now a little bit too short for the windows. We suggested they shouldn’t hang them at the windows anymore, but that didn’t appeal.

They are still hanging there, are they?

Yes. I believe so.

And what year was this? Do you remember?

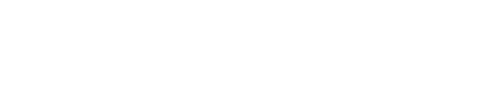

Yes, that was in 1968, because that was when we moved into our new house in Ealing to get more room for the work. In the evenings the Indian boy would be telling our fortunes – all tinged with the mystiques of the East. It was wonderfully entertaining though. He said he saw me in a Palace! Lastly came putting on a lining which had to be done flat and full size. Seven metres by fifteen metres. And the only place that that could be done was in the bottom of the swimming pool in the nearby town, which was emptied especially for our purposes. And the townspeople came in and stood round the swimming pool looking down at us.

Why the swimming pool?

It was a question of getting a space that was large enough.

That was enclosed?

That was enclosed, yes.

I see. Are there pictures from this?

Yes, we’ve got some quite good ones. All the girls were in bikinis, of course. There’s one that includes Eva-Louise and Rinske from Holland, who now lives in Australia, and Naoko from Japan. And another one with Susan and Mick who had been working with me for an awful long time in Ealing.

So this is Noboko?

No, Naoko. Her family name is Futami.

Naoko? Excuse me.

Yes, that’s right. And she was a very special person. All were good, marvellous company. It was great fun doing this project, all of us staying there and sharing everything – house, gardens, work and play. Finished?

No, it’s okay.

To get enough space for us Eva-Louise’s mother had had one of the outhouses made into a guest apartment for the youngest members of our team.

Sounds like quite a production.

Oh, it was, it was nice. I think it was well worth doing, even though the curtains are still very weak. They won’t last very long.

Do you think that the washing actually removed the fire retardant?

As far as we could tell. Of course, we didn’t have quite as many facilities then as we have now. But as far as we could tell. We certainly knew that it was neutral after the washing.

Well, I don’t have any more questions…

Well, do you want to know other exciting projects?

Yes.

I think I told you about Tipu Sultan and conserving that great collection known as Tipu’s Kit for the Lord Chamberlain’s office?

I don’t think it’s been recorded. Not on tape, anyway. You’ve given lecture talks on it.

Yes, and I shall be again this year, because I think it is so important to continue to stress the absolute necessity for cooperation between the historian, the scientist and the conservator. I believe that you should not work at all on historic objects, unless this is very much a part of what you do. Because they are historic documents. Each with its own evidence of our past. The chief reason for our enormous interest as conservators in Tipu’s Kit was because of finding that the quilting material of the war coats came from small pieces of Indian shawls. 17th, 18th century shawls. There are very, very few intact examples of such old shawls.

Oh, that’s terrible. I know that’s the way it is, but oh, how amazing.

Yes. I mean this was an outstanding find.

Is there some sort of symbolism? Why did they have to use those?

Well, it could be symbolism. Among the people who advised us was Russell Robinson, who was then in charge of the armour, including suits of armour and related material at the Tower of London. He told us that quilted coats like that were made as coats of forty layers or coats of sixty layers and obviously a sixty layer coat would protect you better than a forty layer coat. But at the same time it would also be a bit more…

Restrictive.

Yes.

In your movement.

Yes. Which could be bad. In my report, which you may have read, you will know that we counted the layers. Russell Robinson helped with this. He said this was the first time he’d had a chance actually of counting layers. You can only do that in conservation. So we counted 23 layers of fine cotton. And then the layers of old shawls. Mostly very small pieces. Some of them seemed to be very clear cut patches. We got to well over forty, towards fifty before we had to stop, because we couldn’t get to the inside without cutting stitches. And we thought that perhaps if it was meant to be a coat of sixty layers, either the tailors had deliberately cheated by using patches to represent layers or it was a generally accepted way of making war coats.

That’s fantastic.

It was a most fascinating project to work on. And I’m sure that you can see how much this very instructive commission has influenced the whole set up of the Centre. I mean if those things continue to intrigue us then we have to be absolutely certain that the people who conserve them know that their discoveries are important. We cannot leave it in the hands of people who traditionally were only involved in repair but had no interest in history or the fact that the objects under their hands might contain very special information.

So that sort of brings us to your plan for getting back into, well, not back into, but doing more of…

Of the ancient techniques. Yes. I really do want to develop the teaching of this. I would like to do more original work on research. Same as you’ve just now been doing on the Egyptian doll. But perhaps it is more important at this stage to teach more people to look. Even if you can’t teach them all expertise in the actual techniques of analysis. Providing that both archeologists and other people who handle ancient textiles all know what they might find. I believe that the ancient textiles would be safer. You know, because then they might be seen by people like Penelope Walton in York.

That’s combining the science end of it with what she can do in the way of dye identification and fibre…

Yes. And weave analysis. Several young people are working in this field now. Gillian Eastwood, who has just married a Dutchman, I think her name is Vogelsang now, Gillian Vogelsang Eastwood. I’m sure that that’s a wrong pronunciation in Dutch.

Now that I think of it, someone like Elizabeth Crowfoot, who’s been working in the field for ages.

Yes, this is what she’s been doing. All the young ones have worked with her. Hero Granger-Taylor, Francis Pritchard, Lisa Monnas.

She’s still working and presenting papers?

Yes, I’m very pleased to say, yes. Her work opens doors and is tremendously important.

Oh my, here comes the Concorde.

Yes. It’s the only plane that rattles the windows at Hampton Court Palace. I wish it didn’t have to come this way. I suppose that’s progress too (laughs).

Yes. And on that note, I thank you very much, Karen. It’s been fun, I’ve enjoyed this interview.

Yes, I’ve enjoyed it too. And be sure that if anything is done with this that you record, too, my great admiration and respect for the many people with whom I’ve been working over the years. Shiela Landi, who’s been very closely involved. And Mechthild Flury-Lemberg in Switzerland who accepts our students as interns after their exams to give them further experience in practical work and how to understand what they find when they know how to look. And of course the people who started it all in Sweden and my colleagues in Denmark. Without all of the people who’ve been working in this field, we wouldn’t really have got very far. Agnes Geijer, Louisa Bellinger, Margarethe Hald. In Denmark, Else Østergaard’s work on the analysis of fibres and weaves is perhaps some of the most important work that has been done by a conservator. Her work and that of Mechthild Flury-Lemberg at the Abegg-Stiftung is behind my conviction that conservators who work from a background of investigative skills have most to contribute.

Well, thank you.

Thank you.

Postscript

During the ten years since 1975, the Centre has moved forward with great speed. It has progressed through five interdependent phases with some blind alleys being discarded on the way. This year – 1985 – The Centre is about to move into the last phase with which I shall be concerned. There has been much talk about consolidating our achievements and moving at a slower pace which makes me feel a need for caution. I believe that the world will continue to change and the Centre will need to keep up with new ideas and developments in other places, and I fear that consolidation – being a form of stagnation – can only lead to complacency which is no good to anyone – least of all a new profession. Open minds are essential to further progress.

Editor’s note

These interviews were conducted in July 1985. In 1991 Kathy Gillis, a second-year Art Conservation student at the University of Delaware, transcribed the audio recordings for the FAIC’s oral history file. In 1992 Karen Finch added handwritten notes to the transcripts with corrections and additional information. In 2021, when publishing the transcripts on this website, Stephen Cole corrected some typos and added the highlights to show where Karen’s notes deviate from the original audio interview.

Footnotes

- We should also take into account the problems of storing objects that require different treatment and conditions to the rest of a collection.

- The chemicals used for the flameproofing had changed from exposure to sunlight and the ozone over New York. This was what had caused the pH too to change and became too low even for wool.

- On advice by Joyce Plesters at the National Gallery in London.

Related posts

- ArticleHow it all began: A life in textile conservation

- ArticleNote on the damaging effect of flameproofing on a tapestry hanging

- ProjectThe United Nations curtain restoration

- ArticleThe beginning of the Textile Conservation Centre

Copyright notice

© FAIC Oral History File housed at the Winterthur Museum, Library, and Archives

You are not currently logged in. Please log in or register for an account or leave a comment as a guest below.