The beginning of the Textile Conservation Centre

- Nov 16, 2018

- By Stephen Cole

- In Articles + Papers

June 24th, 1999

Paper for the last Alumni meeting at Hampton Court Palace, 24 June 1999

Our first alumni meeting was about the dyeing of support fabrics. The meetings were a means of catching up with new developments, relating new experiences – and getting to know about how to organise such meetings.

Mary Brooks asked me to talk about how the TCC began – I thought everyone knew – but Mary still wanted me to tell you from the beginning. I have thought about her request and how the TCC and my way of teaching are really rooted in my upbringing on a farm in Jutland – in a countryside shaped by the last ice age, which even after all the years of farming by my ancestors is much as the ice left it.

My father was a progressive farmer with farsighted views on the affairs of the countryside and an active member of the local council and farming organisations. Our farm is near Viborg, the seat of the Viking Ting, the forerunner of democratic parliaments. When I learned from the Lord Mayor of London, who opened the first TCC exhibition at the Museum of London in 1977, that the City of London is still governed by Viking law, I thought I had come home. My mother ran our large household on Viking lines, expecting everyone to do their share – and everyone did. She was a fine gardener and an innovative housewife. Together my parents attracted the best young people around to work with them as maids and farm-workers. The maids came to learn from my mother, including her seemingly effortless style of running things, that comes from good organisation and good appliances. The farm-workers came because of my father’s reputation. They would stay for one to two years, before going on to agricultural or, veterinary college. They all lived in – I am the eldest of 8 children – everyone as independent and individual as our parents.

In summer the cousins would come to stay. Often we were more than 20 people around the table for every meal. No pressure was put on any of us to conform or behave. We just knew that we were each responsible for how we lived together – as well as for homework and getting to school on time.

My interest in textiles began when I became aware of the 17th century embroideries in our church. They would have been gifts from the owners of Sødal, the manor nearby – perhaps the couple whose portrait still hangs in the church. Our young Pastor, who came to our Village when I was seven, found the embroideries in the loft and had them sent to Rosenborg Castle in Copenhagen for repair. They came back the year I attended confirmation classes and we had a preview before they were ceremoniously put in place. I had done a bit of embroidery by then, having been taught by one of our maids when I was five. I always wanted to know how things worked, so first I studied the embroidery techniques and then the repairs and how they interacted with the designs.

We all liked to read. I particularly liked the books on history and science inscribed with the name of my father’s brother, who had died in the Spanish ‘flu epidemic before I was born. The pastor let me work my way round the village library, which he kept up-dated with modern literature and travel books. He left for Copenhagen and his next living at the Royal Naval church when I was 14.

At seventeen I went away to Danish High School, where besides cultural subjects, we were taught about housekeeping, dressmaking and other handwork techniques, including dyeing with natural dyes. This was 1938. One night we sat up the whole night to listen to the broadcasts from Munich – about peace with honour! The next year war started and in 1940 Denmark was occupied by the German forces.

My father died, but despite the war my mother let me go to Art School in Copenhagen; she knew the pastor would help if necessary. The Art School, was then housed in the Museum of the Decorative Arts, Kunstindustrimuseet. I was offered a home with the librarian and her daughter. We lived in a flat designed by Kaare Klint, the architect who had transformed the 18th century hospital into a very beautiful – and practical – museum. Kaare Klint and the librarian were married. He taught me to really look at things and to evaluate what I saw. To him problems solved were gateways to future projects.

Weaving and design subjects were taught by Gerda Henning, whose own work was much in evidence in the museum displays. Her accountant came in to teach us the rudiments of accountancy and management skills. My interest in early techniques were shared by a fellow student, Ninna Rathje. We were allowed access to the Study Rooms of the National Museum, otherwise closed because of the war. There we met Margrethe Hald. She let us handle her re-constructions of the archaeological textiles published in her 1950 Doctoral thesis – and in 1980 in an English Version: Ancient Danish Textiles from Bogs and Burials. Her work inspired us both. Ninna went on to help set up the Textile Workshop at the Historical-Archaeological Research Centre at Lejre near Roskilde. The round weave loom was reconstructed there and the bronze age Peplos dress found in Huldremosen. Ninna also worked on Sprang and tablet weave finds. The TCC Reference Collection contains several examples of her work.

The School organised a visit to Rosenborg – where the embroideries from the Church had been restored. Rosenborg was built by Christian IV (1588-1648) as his summer palace and now houses the Royal collections. The workroom had been set up in 1917 for the purpose of restoring the Royal tapestries. We climbed a spiral staircase to the tower workroom – with windows on all four sides. The tapestries were draped over open-top tables, with parts lying on the floor. We – being weavers – noted that the restoration made the tapestries look as though they were embroidered.

Later I discussed the visit with the Keeper of the Textile Department, who had been to the Pietas establishment in Stockholm. Pietas was set up in 1908 for “the conservation of historic textiles under scholarly control”. I was told about their work and the records of every object conserved, including its nature, condition and treatment. The visit to Rosenborg planted the seeds of my enduring interest in wall-hangings and much later in devising a form of conservation that would not detract from their design. I finished my exams, married Norman, and came to England in 1946.

Quite by chance I was offered a position at the Royal School of Needlework involving the restoration of tapestries and historic embroideries. I felt well-prepared, but I had a lot to learn – mainly about workroom organisation – and the prevailing indifference of my new colleagues to the objects and their history and designs. They saw designs only in the context of how their training had taught them to represent details in new work. Designs of objects that came in for repair were rarely noticed. In tapestry this meant that repairs were routinely anchored in the strongest parts, with no regard to what was depicted, in any case people did not necessarily know the subject because tapestries were usually covered up, with just the small part currently in hand exposed. Repairs were meant to blend into the fabric. It should be remembered that, at this time, such work was judged against the context of work done for the sale rooms, which was not allowed to show any obvious signs of repair.

No records were kept of any commission, not even of the studies prior to making the replica of the Jupon hanging over the tomb of the Black Prince in Canterbury Cathedral.

I watched and learned and made friends among my colleagues who introduced me to the richly differentiated life of my new country and their amazing knowledge of the Royal family and their relations – including the Danish ones. All had tales to tell of attendance at Royal functions and weddings with weeping brides.

Our daughter arrived in 1948 and I spent six happy years as a housewife, shopping in the Portobello Road and with time for making things and weaving. Our friends were all intent on banning the A-bomb – mostly by marching in CND demonstrations, with our babies in the lead in their prams. The Aldermaston marches gave me first-hand experience of how banners are carried and why they wear out in use.

When Katrina was settled at school, I wrote to the Keeper of the Textile Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum, George Wingfield Digby, to say I was a weaver who would like to work with tapestries. I was offered a position in Art-work room. Keepers were responsible for supervising our work on the objects, but the workshops were run by section leaders under a foreman responsible for timekeeping and supplies. This division stemmed from where the V&A was set up after the Great Exhibition in 1851. The academic work with the collections was assigned to the Department of Education. The practical work of maintenance was put under the Ministry of Works.

My first task was joining a tapestry that had been cut in two. I did this, as I had been taught at the RSN, but was highly dissatisfied when it was hung and the join was glaringly obvious – at any rate to me.

Mr Digby gave permission to do the next – heavily darned – tapestry with minimal intervention, first taking out the repairs that were obscuring the design, although not detracting from any monetary value – only patches on the back would detract. Nevertheless, I was allowed to support the weak parts on patches with a neutral shade of yarn for the stitching. This was the beginning of the method that was further developed when Danielle Bosworth joined me in my Ealing workrooms. The Esther Tapestry, now on display in the British Galleries, is a very good example of this approach, I am pleased to say. It was the last commission to be completed in Ealing so you may have sat at it.

When this tapestry neared completion the Textile Department asked me to take an interest in the cleaning of historic textiles, including 16th and 17th century silk and gold work embroidery.

I began by discussing the project with my section leader. He was the restorer of miniatures and wax sculptures and very knowledgeable. We got quite a long way, but I knew I needed to know more and that it was essential to keep detailed records of the condition of the objects to be cleaned and all interventions. I now came up against the division between Art-work room and the Departments, because I needed permission from the foreman to go to the library or any other part of the museum, and he refused to let me spend time on research. As for keeping records – he and most of our colleagues believed in keeping their skills to themselves and saw report-writing as the thin end of the wedge of unwanted new developments.

All of this was brilliantly resolved in 1960 with the establishment of the Conservation Department under the Keepership of Norman Brommelle, but by this time I had left to get back to weaving and design and to attend a chemistry course at Ealing Technical College and a course in textile printing at Hammersmith College of Art.

I left two trained successors at the V&A. By the time they too left Norman Brommelle had taken over and he asked me to introduce the next person in the post to tapestry conservation. This was Janet Notman, who eventually became Head of the Conservation Department at the Burrell Collection in Glasgow. Between us we formulated the tapestry conservation course that I came to teach to six more V&A textile conservators – one after the other. This was how we began teaching conservation in Ealing. Danielle Bosworth came along in 1965 and we soon found that her Art School training from Paris formed a good counterpart to my own more austere Scandinavian background. Between us we began to formulate methods of working that would not lose any historic evidence.

Students began to come from other establishments too. Dr Jentina Leene, who founded the Conservation Research Laboratory in Amsterdam, seconded the next ones, closely followed by Elisabeth Kalf of the Tapestry Workshops in Haarlem and Louisa Bellinger of the Textile Museum in Washington, DC.

Though I was unable to offer a structured course including chemistry and art history, about 85 students of 19 nationalities came for periods of up to 3 years before the TCC was set up. By then we had a waiting list running into hundreds of would-be students. No one paid for tuition. Their work was expected to cover the costs. Some stayed on to work on contracts depending on the commissions available. I was not in a position to pay regular salaries, nor could anyone be considered fully trained, unless the person already had the relevant chemistry qualifications. Throughout this time we relied on advice from the scientific departments of the V&A and the National Gallery. They would analyse any problem we came up against and offer appropriate guidance. Norman Brommelle and Gary Thomson were the respective heads and are owed a vast debt of gratitude.

Our commissions were wonderfully varied – including archaeological and ethnographical textiles, dress, dolls, tapestries, regimental colours, flags and banners. I shall mention a few, as they come into my head – beginning with the raised work casket brought in by Miss Victoria Leweson Gower in her rucksack and now at the V&A; the cassock, doublet and breeches left by Prince Rupert with the Craven family, also now in the V&A; the crown of the Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia, looted by the British when his capital was ransacked, kept at the Wallace Collection and then returned by the Queen when she and Prince Philip visited Haile Selassie; the Cap of Maintenance given by Henry VIII to Exeter Town Council; Disraeli’s robes from Hughenden; the 17th century Doge’s umbrella from Waddesdon; 18th century Chinese painted silk hanging from a Belgian chateau; the painted banners from Sir Francis Drake’s “Golden Hind” at Buckland Abbey; a costume painted by Diaghilev for “The Firebird” from the London Museum when it was at Kensington Palace; Charles I’s handkerchief, also from the London Museum, that had lost his initials in the wash but still had the stitch holes that allowed us to put them back; tapestries from King’s College, Cambridge; riding colours worn by Fred Archer, recently seen again at the National Gallery’s sports exhibition; painted livery banners from Gloucester Museum; the Turkish tent, now in Wavel Castle in Cracow; the “medieval” tapestry, that turned out to have been woven in New York only a hundred years ago; the State Beds from Dyrham Park, Hardwick, Ipswich Museum and Doddington Hall; Tipu’s “kit” from Windsor Castle, taken from his palace at Seringapatam after his death when his palace was over-run by the British in 1799; Coptic tunics from Michael Adda; a Peruvian tunic from Bruce Chatwin; five Burne-Jones tapestries from Birmingham Museum; the Clothworker’s tapestries, that needed several weeks repair done in a week to meet the scaffolding dead-line – I enlisted the textile students at Hammersmith College of Art to get them up in time; the colour defended by the first soldier to be awarded the Victoria Cross; the Mortlake tapestries at Kensington Palace, depicting fashions that were incidentally “updated” by previous repairs; the ship’s banner of Cromwell’s General-at-Arms from the National Maritime Museum; the buff coat worn by General Fairfax from Castle Howard; the 18th century uncut velvet suit consisting of a coat with caned skirts, a waistcoat and a pair of breeches from the National Gallery of Victoria at Melbourne; dolls and hats and strangely cut clothes from the Geffrye Museum, including pearly King’s and Queen’s outfits; and suitcase after suitcase of 18th and 19th century dress from Charles Stewart, that he later gave to the Royal Museums of Scotland and that may now be seen at Shambellie, the house where he was brought up. Charles Stewart also gave a collection of naval dress to the National Maritime Museum, that we were told was a link between the slop shops and proper naval uniforms and the only pieces of their kind still in existence. Every commission added new facets to the teaching and to our knowledge in general.

A commission that became crucial to our understanding of the effects of environmental conditions came along in 1968 and concerned the tapestries that had been the gift of the Swedish government to the United Nation’s house in New York. They were designed by a famous Swedish designer and woven by the prestigious company of Märta Måås‐Fjetterström A.B. in Båstad, Skåne.

The tapestries had begun to deteriorate soon after their installation. When the decay accelerated they had been returned to the makers who were, understandably, mortified and unable to apprehend what had gone wrong. My involvement in solving the puzzle came about through a student, Eva‐Louise Svensson, now Pepperall, who had begun her tapestry training at this firm, preparatory to attendance at Konstfackskolen, the Art School in Stockholm. Eva-Louise had come to Denmark to do an internship with John Becker, the weaver, who wrote Pattern and Loom and who had succeeded Gerda Henning at my Art School. She had stayed with Gerda Klint – as I had – who had suggested that she might benefit by coming to London to study the techniques of the tapestries we were conserving. This was in 1964, and from then on she spent most holidays with us. It was at Eva-Louise’s instigation that I was asked to look at the UN tapestries.

For my visit the tapestries were rolled out as much as space would permit, each being 15 metres by 7 metres. I had to kneel on them to examine them. After a few minutes I became aware of a painful rash on my skin where I had made contact, and realised we would need a chemical analysis before we could proceed. A small fragment was removed for examination at the National Gallery in London and we began to make enquiries about any treatment given to the tapestries at the United Nation’s house. We learned that on arrival they had been flame-proofed as required by law for textiles in public places – though wool by its nature cannot sustain fire.

The firm that had done the flame-proofing could not be approached, but we were able to find out about the chemicals that were likely to have been involved and that these, in themselves, could not have caused the damage. When the report by Joyce Plesters at the National Gallery came through, it stated that a combination of the chemical used in the flame-proofing, together with the strong light from the glass wall where the hanging had been placed and the humid atmosphere of New York, had caused a chemical reaction to form strong acidic products. The pH of the sample was 1. We were asked to deal with the damage, which would include washing to remove the chemical and its by-products – this was fortunately possible. After washing, it would be necessary to reinforce the very weak tapestries. Nylon net, with a thin coating of a new and fashionable adhesive, was chosen as the fabric least likely to interfere with their function as curtains. The net would need to be stitched to the tapestry to give enough support and stitching would take time and a good number of people to get it done in the time-scale suggested by the Swedish Government – who were paying for our work. A lot of space was obviously needed. Eva-Louise’s mother offered their farmhouse near the coast as our base – with beds and meals as well as workroom space. We got an international team together, most had worked with us in London, one was a fellow student of Eva-Louise’s from Konstfackskolen, another an old friend from the RSN, now the wife of our accountant. The team included British, Danish, Dutch, Indian, Japanese, South African and Swedish members.

Work began at 5am every morning. After breakfast and a spell on the beach, work continued until our wonderful evening meals. We discovered that our Indian colleague had a gift for fortune-telling – though we lost any belief we might have had, when he read my palm and predicted that I would get to live in a Palace! I have since considered whether my 3 warrants for Grace and Favour apartments at Hampton Court Palace qualified him for an apology – except that the apartments were for working and not for living in.

We learned a lot from that commission, but I hope we shall never again experience the destruction through ignorance of a gift that had been created with so much skill as a monument of our time. Together the unique textile commissions that we undertook in Ealing, and completed with help from so many students in various stages of training, convinced me that the first step towards saving the historic textiles in our care was a sound training in the common denominators of all textiles, namely fibres, dyestuffs and finishes, and that this should go hand-in-hand with an understanding of the environmental forces that are decisive to the survival of any artefact.

Bit by bit the workroom became businesslike. Norman kept the accounts and presented them to our accountant for tax purposes. Our sister-in-law, Greta Putnam, joined us to do letters and invoices and much more. Early in 1969, when the first Esther tapestry from the V&A came along, I was able to invite Danielle Bosworth to come on a daily basis and be responsible for the practical training in tapestry conservation. She has a wonderful ability to get her students to do as good work as herself, and she made it possible for me to concentrate on the survey from 1969 to 1971 of all the textiles on public view at Knole Park – with curatorial guidance from Donald King and other members of the V&A Textile Department. The National Trust eventually asked us to undertake the conservation of the King’s Bed which belongs to the Treasury. I had first come across its intricate and very deteriorated Lampas weave hangings, when I worked at the RSN, and knew this was too large a project for our small group and I suggested the conservation be undertaken in situ as a volunteer project. Our first volunteer was Nancy Kimmins of the Embroiderer’s Guild. She and her husband helped with devising a safe method of unpicking old repairs and keeping in place the three layers of the Lampas weave. The methods had to be suitable for volunteers with embroidery skills. Eventually one of our members was designated to go to Knole Park to run the workroom which was set up in 1974. When the TCC became a reality and took up all my time I had to retire from the project and hand over the supervision to the V&A. Our curatorial advisors also included John Nevinson and Janet Arnold. They would come to look at new commissions as they were brought in by their owners or curators and show us what to look out for. Janet would detect alterations, such as to the quilted dress from Snowshill that she later included in her first Patterns of Fashion. It was when we were working on the Hever doublet, now in the Royal Museums of Scotland, that she said that no garment that had been restored held any interest for her – a statement that reinforced our set of rules to prevent conservation from being damaging to historical research.

I began to speak of an organised training in textile conservation already in 1964 at the first IIC Conference on textiles, held at Delft University. The conference was conducted by Jentina Leene, then the Director of Textile Research at Delft University. Stella Mary Newton was there too, and we met for the first time. Stella told me about the course she was setting up in the History of Dress, at the Courtauld Institute of Art. She asked me to teach her students about textiles. The time to get this teaching underway came in 1969, prompted by Margaret Maynard, then Louttit, the South African member of the UN team, who is now a lecturer in Art History at Queensland University. I tried hard to get Stella to enlarge on her brief, but she was not to be budged. I would have to decide on what to teach. The students would come to Ealing for one day a week during the first two terms, sixteen days in all. I thought about how to teach such a vast subject in what seemed to me an incredibly short time, and decided it could only be done by guiding the students to work on their own, but in an organised manner that would start with handling historic textiles for the purpose of recognising their techniques and materials. Design would be related to available objects.

I began by deciding on a theme for each of the 16 weeks that would include a study of the commissions currently in the workroom and their place in the development of textile techniques and the collection I had somehow acquired – not because of being a collector, but because each piece had been given to me or made for a reason. There was embroidery worked by my mother as a young girl, my own samples from High School and Art School, Ninna’s research work, ancient bits picked up in the Portobello Market when we lived nearby, special pieces from Miss K R Drummond who sold books from her house in the next street and liked to pick up textile samples on her travels, and gold work samplers from Margaret Holden-Jones. Other friends and colleagues too had begun to believe I was a collector – including Doris Bradley, who did our upholstery and later gave her tools to the TCC – and then there were my books and manuscripts and postcards of textiles and textile techniques. A long time after this came the “rag bags” from husbands of friends who had died. One contained several pieces of 17th and 18th century silks. Together the pieces came to form the core of the TCC Reference Collection.

For the teaching I acquired 16 boxes and filled them with my choice for each theme, but we had to postpone the teaching for a year because I had to have an operation for kidney stones. When the course finally began the History of Dress students would arrive at 10am and begin with coffee in the kitchen to recover from their long journey to Ealing. We would spend the morning discussing the study carried out since the previous week and examining the content of the present week’s box, before each choosing a subject for further study during the coming week.

The afternoons would begin in the workrooms. Everyone knew each other, because we always had lunch together. We would discuss each commission and how it was made and had worn and the conservation in progress. Sometimes the students would try their hands on this themselves, usually on their own pieces or pieces from the reference collection. Over several courses they completed pieces like the pierced work apron that I had been given after a holiday in Prague to visit two Czech students. The person who gave it to me did not know from where it originated, but I have since come to believe it is Chinese, made for the European market. It is worked in a strange and obviously commercial technique involving printing with flour paste containing quicklime that made it heat up with friction. They would also do tablet weaving and sprang and the loom would be set up for as many weaving techniques that we could fit in to the time.

Each group was wonderful to teach and quick to understand and we all learned more than anyone could have envisaged – except possibly Stella Mary Newton – who, like me, was aiming at the interchange between future historians, scientists and conservators that comes from learning together as students.

Early in 1971 circumstances forced me to rethink our position. The delegation of duties because of my kidney operation had led to a 4-year waiting list of commissions. Coping with this amount of work would require drastic – and unpalatable – changes, including cutting out teaching and research. Everyone would lose interest, including me, because to me objects from the past are documents of history to be treated with respect and I can see little point in keeping things, unless we intend to put them in context with their making and purpose.

Space was getting critical and so was safety. Textiles of every description had become valuable enough to attract unwanted attention. We had to refuse any more commissions, and we had to have locks put on all windows as well as the doors – 34 in all. But despite all precautions I knew we were very vulnerable.

Up until this time I had expected that the plans put forward by the newly formed UKIC, for a National Conservation Centre, would go forward and we would join in when the time came, but I had begun to realise that this could not happen within a foreseeable future. I still believe in this concept.

After long discussions three of my associates, including Greta Putnam, helped to formulate a proposal for a National Institute for Textile Conservation. The proposal was circulated among our clients and a meeting was called in our house, chaired by Donald King, now Keeper of the V&A Textile Department, who became our first President. There were representatives from the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, the Museums Association, the National Trust, the Historic Houses Association, as well as the V&A. The Pasold Fund acted as ‘pump primers’ – their words.

A decision was made to support our proposals and an ad hoc committee was formed, consisting of Donald King, John Nevinson and Alun Thomas who, mercifully, changed the name to the Textile Conservation Centre, the TCC. They began by putting together our Memorandum and Articles for presentation to the Charity Commission, because only charitable status would give access to funding.

The Charity Commission grinds exceeding slow, so it took 4 years for the TCC to come into existence. However, our Memorandum and Articles is a solid document and it all worked, though some associates lost patience. The ruckus of their departure lost us a large part of the first year’s funding. We survived this problem as well as the long wait, thanks to the waiting list – we just kept on working our way through it – with the proceeds paying for our campaign.

We were greatly cheered in 1973 when Stella got agreement from the Courtauld Institute to let us start a 2-year Postgraduate Pilot Course in Textile Conservation, funded by the Leche Trust. The Technology Department offered the science teaching and the V&A Textile Department a comprehensive course in Textile Design History, with contributions by all its members. We were pleased to be allowed to invite the History of Dress students, now taught by Aileen Ribeiro, to share the V&A course, which we felt to be a confirmation of all our plans.

More people became involved. Dawn Muirhead became our first Company Secretary – she and other supporters brought along VIPs from many places. We had visits from Members of Parliament intrigued by “being nobbled with coffee and Danish pastries by an Ealing housewife”! Our visitors included Viscount Eccles, then Minister of Culture, who was intent on getting the Crafts Advisory Committee set up. He was concerned that we had no conservation scientist of our own. I believe that it was his interest in this aspect that led to the grant from the Leverhulme Trust for the employment of a full-time conservation scientist. The British Museum suggested Dr Anthony Smith, who came to work with us soon after our move to Hampton Court Palace, and stayed for seven happy years.

While we waited we got on with the search for premises. I tried Gunnersbury Park that had a whole mansion empty and Boston Manor and the only 17th century building still visible in Acton, Oak Town of Saxon times – even Buckingham Palace, which we were told did not have the space. Publicity made people aware of our quest and offers began to come from further away. One came from a former V&A colleague, John Lowe, who had been invited by Edward James, the owner of West Dean, to turn the buildings into a College for Country Crafts. They would give us space to run a one-year course in Textile Conservation on the pattern of their other courses. I did not think a one-year course would be enough for textile conservation, and suggested they teach a preliminary course in tapestry weaving instead – nothing to do with conservation, but a straight forward course in tapestry weaving that would be about handling large looms and large hangings and how to turn artists’ sketches into tapestry cartoons. This idea appealed and I was asked to suggest someone to set it up. I suggested Eva-Louise, who was now in Paris weaving tapestries to designs by French painters, interpreted into tapestry by her. Eva-Louise accepted the offer, wound up her position in Paris and came to West Dean in 1973 to start the preparations. She put a course together, designed the looms and supervised their construction and then taught the course for two years. Eva-Louise was also responsible for the first 8 tapestries woven to designs by Henry Moore.

Stephen Cousens and Caroline Clark, who were among the first to join our new Tapestry apprenticeship courses when the Centre was eventually set up, came from the courses taught by Eva-Louise.

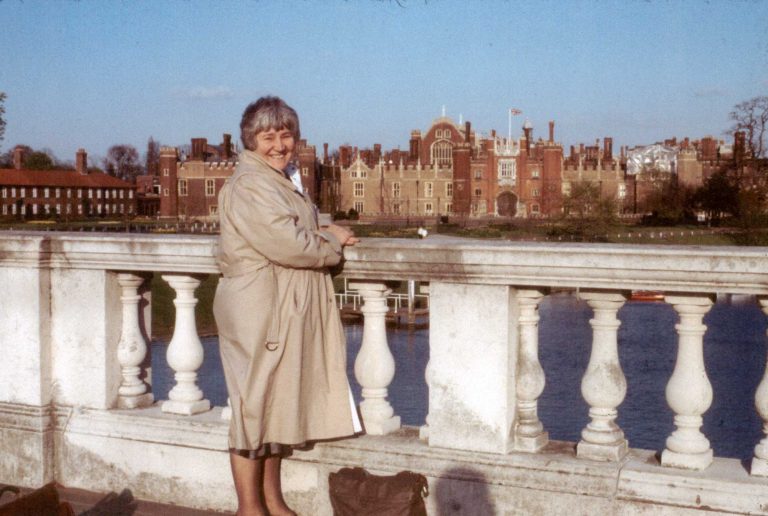

The next offer of premises came from Professor Michael Jaffe, Director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. He offered us Whittlesford Mill on behalf of Sir Hamilton Kerr, after a wonderful lunch attended by Donald King, John Nevinson and myself in his rooms behind the half-circular window overlooking the green at Kings College. On the door was a picture of Christian IV of Denmark – a gesture that I really did appreciate. We accepted his offer and began to negotiate conditions. We realised that we would need to raise £250,000 – then a huge sum – for alterations, equipment and an endowment. I had become even more concerned about security and did not like the prospect of fund raising focusing further publicity on our house. I spoke about this to Vivian Lipman, Under-secretary of State with Responsibility for Historic Buildings, whom I had met in 1972 while giving evidence on the need for textile conservation to the Standing Commission for Museums and Galleries. This meeting was chaired by Lord Rosse and called by Barbara Granger‐Taylor, who throughout our campaign saved me from the worst pitfalls of my ignorance of proper procedures. She also introduced Jenny Fitzgerald‐Bond, who in due course left her ILEA lecturing post to join the tapestry course and to teach embroidery techniques. Strands were coming together and a lot of people became involved in our search for a safe place to work and raise funding for the next step, but nothing happened until the autumn of 1974 when I had a phone call from John Thorneycroft, architect to Hampton Court Palace: “How much space do you want for that thing of yours?” “10,000 square feet”. “Oh!… what would you say to 3,000 for two years?” I thought for fully half a second and said: “Move in?” The unspoken question was noted and John Thorneycroft was as good as his, unspoken, word. He became a trusted friend and when the two years were up and we were allowed to stay, helped us to get more space. I retired when I held the three Grace and Favour Warrants, and the Centre very nearly had the space I had asked for.

On 14 April 1975 we moved into Apartment 22 in Base Court. We brought all my equipment, tables, chairs, frames, tools, looms, a lace-making pillow and bobbins, books, reference collection and the small microscope with an attachment for macro photography that my fee from the Courtauld Institute had enabled me to buy. There was also all the remaining commissions on the waiting list, including tapestries from the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, the National Trust and the V&A, Michael Adda’s Coptic tunics – two van loads in all. We could not let anything out of our sight during the move and everyone helped to make sure nothing was lost or damaged, staff and students from America and Guatemala and all over Britain, and most of all Norman who, though he rarely complained, was greatly pleased to get the Nation’s treasures out of our home – and in particular not to have to worry about their safety any more.

Some months after this momentous day, we had a message from Professor Jaffe to say it had been nice knowing us but the Whittlesford Mill project had been given funding for painting conservation, so our arrangements were at an end.

By this time, we had convinced the Palace that we were worth holding on to – at least for the time being – and the Lord Chamberlain gave us permission to stay when the two years were up.

Funding soon became of overwhelming importance. The politicians, who had promised official funding to the TCC as soon as it was up and running, went out of Office. Inflation was rife. The Assurance by the TCC Council that I would not have to deal with the funding and fund-raising, evaporated. It had been promised to allow me to concentrate on developing the Courtauld Institute course and setting up the workrooms that were to become the province of Danielle, our first Conservator/Tutor. The second half of the grant for equipment, awarded by the Crafts Advisory Committee, soon to change its name to the Crafts Council, was cancelled when the Whittlesford Mill project fell through.

I am pleased to say that we overcame all obstacles, even the fact that the Crafts Council was unable to fund the course with the Courtauld Institute because their brief was to support the Crafts and not University courses. I understood that they were restricted and put together the Apprenticeship Course in Tapestry Conservation. The Courtauld Institute agreed to let all of our students share the first year, which included conservation science and the history of design and techniques. The Crafts Council did not contribute to the teaching, but did award a third of the first year’s salaries. They thought salaries more appropriate than asking apprentices to pay for their training. Regrettable, since funding would have been available from other sources, and this unexpected cost to us was crippling.

We found that our free accommodation at Hampton Court would be the only form of regular funding we could expect, and that, therefore, since conservation commissions were a very necessary part of paying our way, we obviously had to base our rates for commissions on our out-goings. This was not acceptable to some of our clients, who feared they might be subsidising our teaching.

We kept in mind that in other branches of conservation, such as that of paintings and sculptures and even paper, people did get paid at a fair rate, and we got on with updating the estimates for the rest of our commissions from Ealing – at any rate those we did not consider suitable for teaching for which we only charged a nominal sum for overheads. Most of our clients were able to accept the revised estimates – perhaps because we were not the only ones who wanted a fair rate for fair work! Other conservators too were updating their commissions.

We came up against many established conventions, and it was often uphill work. Sometimes we were made to suffer – as are most pioneers.

I soon learned that we had only ourselves to rely upon – and to add fund-raising to my other duties – with no humility whatsoever. I saw the TCC as badly needed and funding as our due. My attitude may have been a residue of my upbringing in Denmark where the State covers 85% of the teaching costs of established courses, or it may have been coloured by the thought that since textile conservation is the second oldest profession in the world, the cultural implications alone should make the textiles in our museums be worthy of preservation as historic documents – or maybe it was hardened by the fact that all TCC graduates found jobs and were soon highly appreciated.

Whatever – I got quite good at fund-raising and became immensely grateful to all the Foundations and private donors who helped the TCC to survive during this critical time. Besides the ones already mentioned, I shall name a few more – including the Radcliffe and Ernest Cook Trusts, and their representative Barbara Whatmore, whose long-term views gave much insight into how to set about things. Then there was the Pilgrim Trust with Alastair Højer Miller and the people from the Livery Companies, and so many more. The number of Foundations who helped grew in numbers and I am overjoyed to see their familiar names in the long list of present day supporters. I know that their support is best justified by our results and I hope they are pleased with what has been achieved.

The Victoria and Albert Museum was of great importance to the TCC. It was closely followed by the National-Westminster Bank when they seconded John Mercer, but even with his careful counsel and support, I think it is fair to say that, without my 5 years as a civil servant, the TCC could not have survived. I learned about being part of a large organisation there and the patience and diplomacy that makes it work – at least I learned to appreciate these qualities. Donald King’s “…be flexible, Karen” will ring forever in my ears – alongside John Mercer’s: “with respect…” And Norman’s patient sighs. They all wanted me to take one step at a time. I did try, but found it quite impossible. Every strand was interwoven with everything else – just like mixed farming.

Hampton Court Palace gave the TCC a beautiful and prestigious home. We greatly appreciated the kindness and forethought we met there, right from our ceremonial welcome by the Chaplain and the Housekeeper and by General Sir Rodney Moore, the Chief Steward. He made sure we were looked after and protected, including from time-wasting media intrusion and politicians, who wanted us to give way to an upmarket hostel for visiting dignitaries. Sir Rodney’s example taught me to cope with situations I never dreamed about, even the arrival of unexpected Royal visitors.

His successor, Lord Maclean, when he was the Lord Chamberlain would ask greatly pertinent questions at his periodic inspections of the Palace. I got carried away by his interest and would elaborate on my answers until I caught the dismay on the faces of his retinue behind – all in a row looking at their watches!

Until we got our last Grace and Favour Apartment we were allowed to use empty apartments when we were desperate for space, and once the Security Officer found a space outside the Palace grounds – with the Fire Officer in attendance – to let us remove chemicals causing damage to an important English tapestry from Weston Park having first extracted a solemn promise to say “No” to any more dangerous commissions. We were helped in so many ways – not least by the gate keepers and the warders, with their never failing courtesy to us and to all our visitors.

That the TCC grew and prospered is more than anything else due to the teamwork of students and staff – in Ealing and at Hampton Court. Their enthusiasm and youthful acceptance of the constant changes necessary to move from phase to phase of my accelerated vision, was the chief ingredient in making the TCC come together in all its diversity. All had to work harder than they could ever have expected. Very recently, last May, I was reminded of this by a TCC graduate now at the Burrell Collection in Glasgow. We were attending an international meeting on archaeological textiles in Edinburgh, and having lunch together when she said about how much the course had meant to her. She had indeed felt overworked as a student, but wanted me to know that even in her very first job she had been on top of the work right away because we had taught her what she needed.

I have now described how the TCC got started. Many more people were involved, including members of the Council and Executive Committee, our Administrators beginning with John Mercer and Peter Hadfield, our wonderful volunteers like Joan Anstead and Esther Carvalho, who taught us to understand how Jewish vestments were used, and my neighbour Heather Campbell, who became the first TCC secretary and has now helped me to write this account. But first and foremost there was my husband, Norman Finch. Without his enormous practical contribution there could have been no TCC – and that is quite apart from the support in every crisis given by him and our daughter, Katrina.

This was just the beginning, and now thanks to Nell Hoare and Mary Brooks and our new relationship with Southampton University and Winchester College, the TCC will go on to much greater heights, including bringing to fruition the plans that inspired Stella Mary Newton and myself in the first place, namely for curators, conservators and designers to start their careers together and learn to work in unison on developing all the different strands of study and presentation to the public that we shall need in the Twenty First Century.

Author’s note

This was the beginning. The TCC is now housed at Glasgow University, who may have different perceptions. I am no longer involved but I shall never cease to wish for its continuing growth and success.

Karen Finch

2010

You are not currently logged in. Please log in or register for an account or leave a comment as a guest below.